How the Fourth International fought World War Two

As the anniversary of the end of World War Two is celebrated, the world’s leaders are again recruiting soldiers and arming them with horrific new weapons in preparation for new conflicts, and possibly yet another, even more brutal world war.

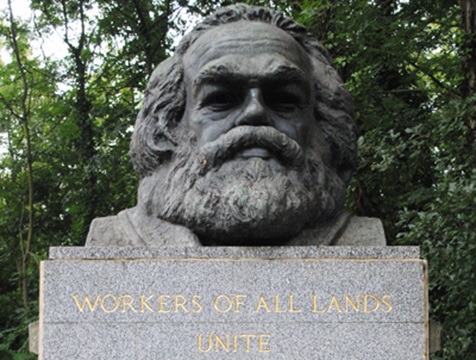

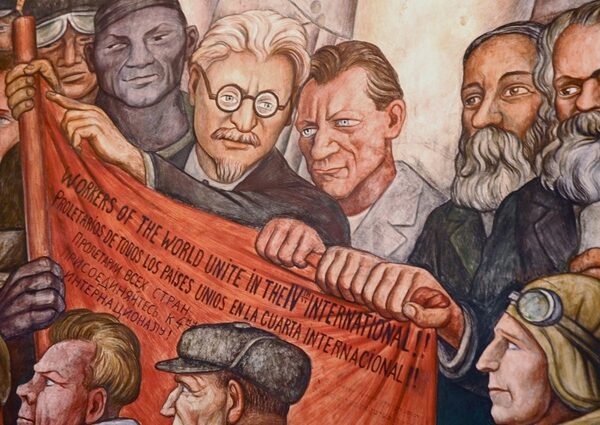

This article examines how Trotskyists worldwide struggled, ‘despite all hazards’, to build the slender forces of the Fourth International (FI), intended to assist the working class to overthrow capitalism, and the bureaucratic, Stalinist elite in the USSR and replace them by genuinely democratic, international socialism to end poverty and war forever.