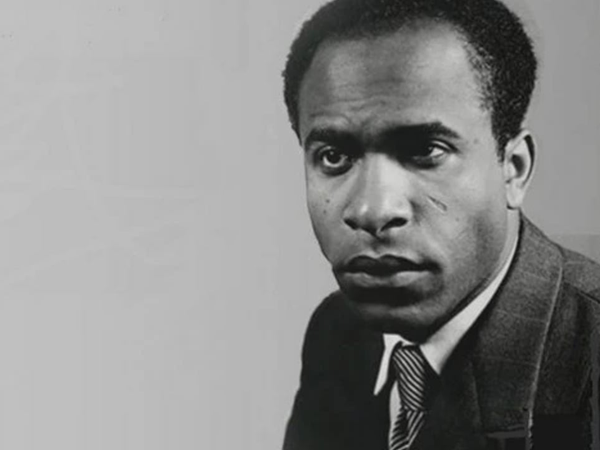

This week marks one hundred years since the birth of Frantz Fanon. A psychiatrist by profession, Fanon as a writer explored the morbid delusions and hallucinations of racism, empire and capitalism in celebrated works such as Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961). The latter book title (‘les damnés de la terre’) is drawn from a line in the labour anthem ‘The Internationale,’ reflecting the fact that Fanon was one of a wave of remarkable Afro-Caribbean socialist writers, including CLR James and Walter Rodney.

Frantz Fanon wrote with conviction. His statements were bold, categorical and challenging. His voice still rings out clear today, whether raised in anger against racism or in support of peoples struggling for freedom. A Dying Colonialism is the latter, a portrait of the Algerian people in struggle. Published during Algeria’s war of liberation against the French Empire (1954-1962), its focus is on how the experience of a liberation struggle had changed popular consciousness. Although he came from the French Caribbean colony of Martinique, he writes of the Algerian liberation struggle in the first person plural (‘We…’), showing an internationalist outlook rooted not only in a common struggle against the one imperial power, but against global imperialism.

This conflict was notorious for the use of torture and other atrocities by the French colonial authorities. While Fanon deals with this matter, the Algerian people appear for the most part as protagonists and not as victims. And although it is an account of armed struggle, there is nothing about troop movements, weapons or tactics. It focuses on culture and psychology: clothing, radios, family relations, medicine. These innocent cultural artefacts become sites of proxy conflict. The people of our own time are no strangers to this kind of thing, as when US conservatives boycotted Bud Light as a roundabout way to attack trans people, or when Zionists interpreted a Superman movie as propaganda against their cause.

‘Algeria Unveiled’

Another 21st Century example is of how public debates have raged over the burqa, the face covering worn by some Muslim women. These debates might have been a lot shorter if more people had read Fanon. He is very interested in the veil worn by Algerian women and instead of judgement or scorn he simply gives an account of what it meant in the context of the struggle. It was first used as a line of attack by the colonisers who, in the name of liberating women, sought to ‘unveil Algeria’ (The United States tried to defend its twenty-year occupation of Afghanistan in a similar way, by arguing that they were there to protect women, as if the US Marine Corps were some kind of intersectional feminist collective).

But French men who wanted to uncover Algerian women almost always revealed in their crude remarks that feminism was the last thing on their minds. Fanon portrays the French effort to ‘unveil Algeria’ as a neurotic obsession and shows how this campaign did nothing for the liberation of women. It actually entrenched patriarchal customs by associating them with anti-colonial resistance.

Nonetheless, the role of women in Algerian society underwent huge changes in the 1950s. These came about not through any initiative of the coloniser but through the mass struggle. Women members of the independence movement would go about unveiled so as to pass unchallenged carrying weapons or messages in the European and Europeanised quarters of the cities. This would be the first time in their lives that they were in public unveiled, a profound experience that they undertook on their own initiative. On the other hand there were situations where a woman could use a veil to pass unnoticed.

Whether veiled or unveiled, revolutionary activity would shake the structure of the traditional Algerian family, as countless fathers came to terms with the fact that their daughters were away from home for days, weeks or months at a time, staying with unknown men in safe houses or guerrilla camps. The fathers of women resistance fighters not only came to accept this but to be proud of their daughters for taking on life-and-death responsibilities.

Guerrilla Radio

Likewise, the radio was initially rejected by the colonised who saw it as an instrument of the coloniser, linking the settler with his French homeland and spreading his propaganda. Fanon describes with total sympathy how difficult it is for the colonised to be simply ‘objective’ and ‘neutral’ when their own culture and collective dignity is under threat.

But when Algerian national liberation fighters set up their own radio stations, and the French colonial government banned these stations and jammed their frequencies, Algerians became very keen on the radio. Tuning in to listen was itself a kind of anti-imperial struggle in which the masses could participate, as they had to tune in to a particular frequency then change to another when the first was jammed, and so on, in a cat-and-mouse game with the authorities. Each person who managed to catch the news would pass it on by word of mouth to many.

Points about how liberation movements in the past have related to technology like the radio could give us some general ideas on the technologies of our own day. Maybe it has happened in reverse with us. Ten-fifteen years ago there was a utopian attitude around the potential for social media to advance progressive causes but now there is a growing disgust with social media as it becomes more obvious that big tech are poisoning minds and eroding culture for their own profit. Blind reactionary hatred is promoted, even on platforms that are not owned by manic Nazi-saluting cranks. Attitudes have zigzagged, showing that it is just as difficult for us today to be objective about new communications technology.

Medicine

In a similar way the section on medicine made me think of the anti-vaccine and anti-science consciousness in our own time. The colonised were inclined to reject modern medicine alongside modern communication techniques. Algerians were suspicious and uncooperative even toward well-meaning and objectively good health initiatives. Commentators at the time put it down to the ‘native character’ or a ‘fatalist’ attitude to health. In reality, of course, it was rooted in very real and immediate conflicts. A country that conquers another with fire and slaughter can’t expect to be trusted when it comes to health. We also see another example of how innocent things become battlegrounds: if the colonised people concede that modern medicine is good, actually the coloniser takes his good faith as an endorsement of the whole colonial project.

And then there was the role of doctors in torture and repression. Doctors at the beck and call of the French military would treat a prisoner who had been tortured to the brink of death in the knowledge that he would be going right back into torture as soon as he was fit enough. Some doctors would use barbaric techniques of torture themselves, such as ‘truth serums’ that would cause brain damage.

And just like with the radio, when the French banned certain medical products in order to keep them out of the hands of the guerrillas, the public began enthusiastically to seek these products out, and smuggling networks sprang into being. Public health advice coming from the liberation movement’s leadership, or from ‘our own’ doctors associated with the movement, was taken on board very seriously.

Modern medicine coming from the enemy was rejected, along with communications technology and the liberation of women. But these same things were championed when they emerge organically from the initiative of the people themselves, in opposition to the coloniser.

Minorities

Fanon devotes one of his five chapters to the question of winning over Algeria’s European minority along with other minority groups such as Jewish people. He urges that several hundred of the most powerful settlers be kicked out of the country, and as for the professional torturers and murderers of the security apparatus, they must be kept under observation and treated by psychiatrists. But as for the rest, he argues for all minority groups including Europeans to be accepted as an integral part of a new multi-religious and multi-racial Algerian state. He includes an entire appendix which is an account of revolutionary activity by an activist from a French background, and spends considerable time on instances where even settler-colonist farmers aided, armed, fed and sheltered the guerrillas.

In this book and elsewhere Fanon makes a case that violence can be justified. But that’s in the context of his universalist and humanist vision of decolonisation.

Conclusion

Colonialism is alive and well, most obviously with the Israeli state’s genocide in Gaza, ethnic cleansing in the West Bank, and endless aggression, all with unlimited and unconditional support from the United States. Fanon was writing in a more optimistic time, when things were moving powerfully in the right direction. Following the Russian and Chinese revolutions, the defeat of fascism and the exhaustion of the old European empires and that of Japan, one nation after another was winning political independence. Unfortunately, without also overthrowing capitalism, these countries continued to be dominated and strangled economically by imperialism – demonstrating how anti-colonial struggles are bound with the struggle for international revolutionary socialism.

To read Fanon on the centenary of his birth is refreshing, a moment of escape from the present and a reminder of what is possible in the future.