By Drew Frayne, Socialist Party Ireland, 21 February 2025

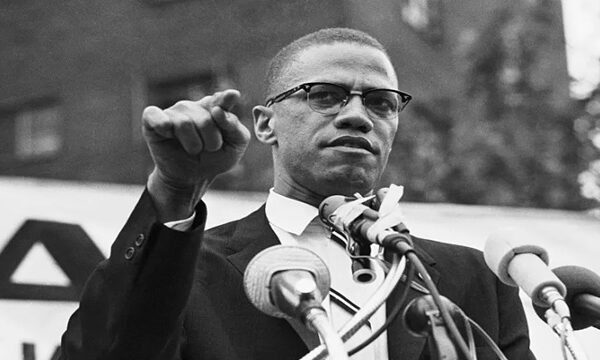

Sixty years ago el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, known to the world as Malcolm X, was murdered. His life is a map of 20th Century racism, and resistance to white supremacy, in the US and across the world.

The personal and political life of el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, known to the world as Malcolm X, is a map of 20th Century racism, and resistance to white supremacy, in the US. His powerful life holds many lessons for revolutionaries today – particularly “the white man” (which includes the author of this article).

From his childhood experiences with white supremacist violence and state oppression and evictions, to his rejection of soft-left reformism of JFK, he understood that the existence of Black oppressed class in the U.S. was not an accident—it was a necessary foundation for the U.S. empire.

Unlike liberals and even many on the left, he refused to argue for what was merely “possible” under the system; he fought for what was necessary. His evolving politics later in his life – embracing a more internationalist, multi-racial, anti-imperialist, and pro-women perspective – demonstrated a radical clarity that remains essential for revolutionaries today.

Malcolm’s deep distrust of white liberals and the left was well-earned. Marxist organisations struggled to recruit Black members – Stalinist and Trotskyist alike – largely due to internal racism. Unions historically sidelined Black struggles, treating them as secondary to economic issues, and failing to confront racism within their own ranks. During his lifetime, major unions locked Black workers out of economic power, helping to create divisions within the working class.

Today, Marxists tend to focus on correcting his ideas, speculating on whether he would have become a socialist, rather than grappling with why he never did.

The consequences of the left’s failure to integrate race and class have only deepened in the 21st century.

The subprime mortgage crisis disproportionately targeted Black communities, widening racial and economic inequality. The Great Recession fractured the working class further. The absence of an organised and militant left in the U.S. has allowed reactionaries like Trump to exploit resentment while billionaires like Elon Musk posture as anti-establishment figures.

The left’s failure to prioritise Black struggles isn’t just a moral failure—it’s a strategic one. Without rebuilding trust and making antiracism central to working-class politics, the left will remain irrelevant, ceding ground to reactionary forces. The state’s repression of Black anti-capitalist movements, from the Black Panthers to MOVE (the Philadelphia based Black anarcho-primitivist group bombed from a helicopter by Philadelphia PD in 1985), should make it clear—antiracism combined with anticapitalism are the ruling class’s greatest fear.

Yet there is hope. Young white people today, particularly young women, are more anti-racist than ever, and their understanding of intersectional oppression gives them a powerful foundation for solidarity. The Black Lives Matter movement showed that meaningful unity is possible, with young white activists taking real risks alongside Black organisers.

Now, the global movement against the genocide in Gaza is radicalising another generation, exposing the hypocrisy of liberals and the deep ties between imperialism, white supremacy, and capitalism.

We are not in a revolutionary moment like the 1960s—we are in a period of far right, racist and misogynist authoritarianism ascendancy. But that only makes the stakes clearer. Malcolm X’s greatest lesson was that the struggle for liberation demands organisation, clarity, and action. The power to smash racism and capitalism lies in our hands. We must seize it and organise.

Malcolm’s Early life up until Prison Sentence

Starting before he was even born, Malcolm X’s family was on the receiving end of white supremacist terror. His father, Earl Little, was a Garveyite, a believer in Black self-separatism, and African repatriation. The simple Garveyite creed, of advocating that Black people build an independent life for themselves, made him a target.

The Ku Klux Klan harassed the family in Omaha, Nebraska, circling their home on horseback, smashing windows, and threatening violence. They were forced to flee to Lansing, Michigan, but safety never came – not even in one of the most Northerly states in the US.

Their new, predominately white, neighbours objected to having a black family living nearby and after they took a court case against the Little Family, a county Judge ruled to evict them. The land was for whites only. Earl Little of course refused to move and the situation escalated.

In 1929, their home was burned to the ground, likely by the Black Legion, a white supremacist group active in the area. Earl Little was accused by police of setting the fire himself, in another act of intimidation, although the charges were later dropped. Two years later, Earl Little was found dead, his body mutilated on train tracks. The police called it a suicide, and the insurance company refused to pay out.

Left with nothing, Malcolm’s mother, Louise, struggled to keep the family together for several years, but the state stepped in—not to help, but to tear them apart. She was declared “unfit” and institutionalised, while Malcolm X and his siblings were scattered into foster care.

The young Malcolm X excelled in school, often the only Black person in his class, but racist teachers imposed limits on his future. When he said he wanted to be a lawyer his teacher called him racist slurs and told him to be a carpenter.

The message was clear: America had no place for Black ambition or intellect. Disillusioned, he dropped out of highschool, pushed toward the only paths society left open — cheap labour or crime.

At 20, Malcolm X was arrested for burglary and sentenced to ten years at Charlestown State Prison, Boston, Massachusetts. The sentence was far harsher than the white women who were caught with him. He wasn’t just sentenced harshly, he was made an example. He was given a decade behind bars, not just for burglary but for daring to cross racial lines.

The police pressured the white women he was arrested with to accuse him of rape, but they refused. It didn’t matter. Malcolm X noted in his autobiography that the court seemed more outraged by the fact that he had been with white women than by the actual burglary. The message was clear: step out of line, and the system will crush you.

But prison didn’t break Malcolm—it transformed him.

Malcolm’s Prison Politicisation

In prison, Malcolm found a new purpose. His siblings had continued their fathers’ activism, and through them, he was introduced to the Nation of Islam (NOI). Similar to the Garveyite movement, the NOI advocated for Black separatism – it also framed Black suffering as the result of white oppression and preached self-discipline, and racial pride.

Hungry for knowledge, he devoured books, educated himself, and embraced the NOI’s teachings. After “lights out” he read by the sliver of light that cut into his cell from the corridor, jumping back into bed and feigning sleep when the guard passed by.

He read everything he could get his hands on—history, philosophy, religion, literature. He was especially drawn to Black history, learning about slavery, colonialism, resistance, and the global devastation of the white man.

“I perceived, as I read, how the collective white man had been actually nothing but a piratical opportunist who used Faustian machinations to make his own Christianity his initial wedge in criminal conquests. First, always “religiously,” he branded “heathen” and “pagan” labels upon ancient non-white cultures and civilizations. The stage thus set, he then turned upon his non-white victims his weapons of war.”

“Not even Elijah Muhammad could have been more eloquent than those books were in providing indisputable proof that the collective white man had acted like a devil in virtually every contact he had with the world’s collective non-white man. ” (pg 190-191)

Education became his liberation. By the time he left prison, he wasn’t just free—he was transformed.

It was his political awakening — the moment Malcolm Little began transforming into Malcolm X.

Reflection on US Racism

What happened to Malcolm X and the Little family is a case study in American racism. White supremacist terror worked in tandem with state policies to keep Black families dispossessed across the US. Often resulting in the criminalisation and incarceration of young Black men.

As Black people moved north during the Great Migration, seeking work and a way out of Jim Crow, cops, white supremacists, “regular” white neighbours, and the banks made sure they remained barred from the basic rights white workers took for granted.

The state reinforced this divide in the 1930s through redlining, a system that systematically blocked Black families from homeownership by denying them mortgages and marking their communities as “high-risk.” All of this happened with the generalised cooperation, complicity, and blessing of the white population.

Post slavery, this ensured the development of an impoverished Black working class, while a white “middle class” was propped up as the stabilising base of U.S. capitalism.

The major unions of the era—like the American Federation of Labor (AFL) – actively excluded Black workers, either through outright racial bans or by structuring their locals in a way that kept Black workers locked out of skilled trades.

Even the more progressive Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), while more open to Black workers, often failed to prioritise their struggles, leaving them vulnerable to employer exploitation and racist hiring practices.

Without union protection, Black workers were forced into the lowest-paid, most dangerous jobs, often as strikebreakers—a role they were pushed into, but one that white unions used to justify further exclusion. This deliberate division weakened the entire working class, ensuring that the US’s brand of racist capitalism could continue to thrive, keeping Black workers at the bottom while white workers gained the limited benefits of a rising middle class – “benefits” only in relation to the destitution forced upon Black Americans.

Malcolm X’s Political Transformation: The Nation of Islam

Joining the Nation of Islam while in prison marked a profound turning point in Malcolm X’s life. The organisation provided him with discipline and purpose – a structured home of paternal love and spiritual redemption in a world built to break and shame him. The NOI rejected integration as a path forward and insisted on self-reliance as the only response to white supremacy.

In an America that systematically emasculated Black men like Malcolm, the NOI’s programme was revolutionary: take pride in your identity, depend on your own strength, and build your community from the ground up.

Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, became a father figure to Malcolm X. Under his direct mentorship Malcolm found a renewed sense of honour and pride, countering the dehumanising effects of a racist society.

With his exceptional intellect and flare for public speaking, Malcolm X quickly emerged as the public face of the Nation of Islam. His fiery speeches dismantled the myths of white supremacy, shattering the narrative of a country built on exploitation and dominance.

His powerful oratory and tireless organisation skills were a catalyst for growth for the NOI, attracting large audiences and spurring the establishment of new mosques across the country.

Beyond growing the NOI, Malcolm X reinvigorated the very notion of Black pride for many Black people in the US – Black men in particular. In a society that had long stripped Black men of their dignity, his speeches provided pride, self-respect, and strength. His full quote on how Black people are thought self-hate is worth quoting in full:

“Who taught you to hate the texture of your hair? Who taught you to hate the color of your skin? To such extent you bleach, to get like the white man. Who taught you to hate the shape of your nose and the shape of your lips? Who taught you to hate yourself from the top of your head to the soles of your feet? Who taught you to hate your own kind? Who taught you to hate the race that you belong to so much so that you don’t want to be around each other? No… Before you come asking Mr. Muhammad does he teach hate, you should ask yourself who taught you to hate being what God made you.“

In embracing the NOI, Malcolm X not only redefined his own identity but also helped forge a new path for Black America—one built on the principles of self-reliance, unwavering pride, and the relentless pursuit of freedom.

Malcolm’s rapid ascendency to de-facto “second in command” created a lot of speculation about Malcolm X being the automatic successor of his mentor, something he denied regularly, and made clear in all his speeches and interviews that he was there to preach the word of the Honorable Elijah Mohammad.

This dynamic would soon lead to tension between the two men, much of it fomented by Elijah Mohammad’s sons, who were envious of the power given to X. The NOI had embraced capitalism as a means to raise funds and had a string of successful small businesses that kept the organisation, and its leadership, well resourced.

Pressure Mounts on Malcolm X as his star rises

Racism in America wasn’t an accident – it was engineered to keep Black people subjugated. Far-right racism and state repression operated as twin engines of oppression. Lynching, segregation, and brutal police violence weren’t aberrations; they were everyday instruments used to strip Black communities of dignity and freedom.

A pivotal cog in the state repression machinery was J. Edgar Hoover, whose FBI viewed Malcolm X as a dire threat—feared to be a potential “Black messiah” capable of galvanising a mass uprising against the established order.

Through programs like COINTELPRO, Hoover relentlessly targeted NOI and Malcolm, surveilling and attempting to undermine his influence even prior to his rise to fame – Malcolm X would often “welcome” the undercover agents in the audience at the start of his speeches. Hoover’s fear was clear: a unified, awakened Black populace could dismantle the foundations of the racist capitalist US.

Simultaneously, soft-left reformism distracted many with the illusion of change. Liberal politicians, including JFK, spouted stirring rhetoric on civil rights while their actions were feeble or non-existent.

Malcolm X sharply critiqued this hypocrisy, as well as the peaceful approach of leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., arguing that such strategies were woefully inadequate in the face of systemic violence and racism. Following the example of Gandhi, X argued, was not viable because Black people in the US were in the minority – whereas in India Gandhi’s followers massively outnumbered the occupying British colonisers.

The labour unions had a mixed role, at best, during the revolutionary mood of the sixties. Offering rhetorical support to the movement, there was no consistent attempt to mobilise their members, or to connect them to the workplace struggles that were continually undermined by racism and the presence of an oppressed class of people who the state the bosses could use to scapegoat or act as cheap non-union labour.

But the nineteen-sixties was a time that promised revolution. Malcolm X’s uncompromising voice emerged as a beacon of radical Black resistance in an environment where few revolutionary groups, certainly no Marxist groups at time, appealed to the Black Americans.

Opposition to America’s brutality in Vietnam was mounting. A wave of anticolonial revolutions had rocked the post WW2 global establishment – particularly in North Africa and the Arab speaking nations.

This mood, combined with the growing civil rights movement, gave increased politicisation to Minister Malcolm’s previously spiritual speeches – something which caused the old guard of the NOI great concern. They continually tried to hold him back, demanding he “tone down” the politics and revolutionary edge of his talks.

In this highly volatile political environment, Malcolm X was squeezed on all sides. Within the NOI his relationship with Elijah Muhammad was fraying. The workload was intense and he barely slept. The media portrayed him as a violent thug. There were constant threats on his life from white supremacists. He was constantly surveilled by the sinister forces of the state. And criticism from the liberal wing of the Black civil rights movement was constant. He continued to withstand the pressure, but something, somewhere, had to give.

Break with the Nation Of Islam

Malcolm X’s growing frustration with the Nation of Islam was as much a personal crisis as it was a political awakening. He began to see the NOI’s rigid refusal to engage in genuine political struggle—a stance that confined its message to separatism without challenging the systemic forces of oppression. His disillusionment deepened with the increasingly blatant corruption within the organisation.

A major betrayal for Malcolm X came when he learned of Elijah Muhammad’s abuse of young women in the NOI. He fathered children with several of his teenage secretaries, and later abandoned them – forcing them to bring him to court for financial support. To be a hypocrite within Islam and the NOI specifically was seen as a grievous failure as a Muslim.

After hearing persistent rumours Malcolm X spoke directly with the young women to ascertain the truth. He soon after confronted his mentor with the allegations – and although Elijah Muhammad agreed to seek forgiveness, X’s fate as an enemy of the NOI was sealed from that moment forward.

The chance for the NOI leadership to rid themselves of Malcolm X came after JFK’s assassination in November 1963. The NOI had barred all members from commenting on the assassination, but when questioned by reporter Malcolm boldly declared that “the chickens have come home to roost,” a statement that alluded to the US’s imperial violence.

The NOI used this to swiftly suspend him from speaking for ninety days. Malcolm would split from the organisation before resuming his role as NOI minister.

Malcolm X knew he was a marked man, and tells the story best himself:

“Any Muslim would have known that my “chickens coming home to roost” statement had been only an excuse to put into action the plan for getting me out. And step one had been already taken: the Muslims were given the impression that I had rebelled against Mr. Muhammad. I could now anticipate step two: I would remain “suspended” (and later I would be “isolated”) indefinitely. Step three would be either to provoke some Muslim ignorant of the truth to take it upon himself to kill me as a “religious duty”—or to “isolate” me so that I would gradually disappear from the public scene.“

This rupture was about diverging political strategies and unresolvable contradictions in the application of their core principles – principles which Malcolm still held, but his Mentor had abandoned, or never truly believed in.

It was a profound moment of growth where Malcolm recognised that the fight for Black liberation had to confront not only racial injustice but also the grip of the rotten leadership. In breaking away from the NOI, Malcolm X began charting a path toward a more expansive and radical vision—a vision that rejected superficial reforms and demanded true systemic change.

His struggle with the NoI would draw sympathy from anyone who has struggled against decrepit and bureaucratic leadership within their own organisation. As too would the demoralising lack of solidarity that can come from revealing the failures of the leadership.

Malcolm X was sure that NOI rank and file would leave en-masse once they learned of the leadership’s failures. This was not to be. The loyalty to the leadership and the status quo was too strong, even for Malcolm’s own brother who remained a member of the NOI. Malcolm sought new spiritual and political connection further afield.

Malcolm X on Women – and his apparent queerness

The NOI was a decidedly patriarchal organisation with patriarchal beliefs and practices. Malcolm also held these views, and talked about “our women” and how “real men” should protect their women. However he did recognise what today would be called the “intersectional” dynamic of Black women’s oppression in the US stating in 1962:

“The most disrespected person in America is the black woman. The most unprotected person in America is the black woman. The most neglected person in America is the black woman.”

Malcolm still held conservative and patriarchal views on women after his departure from the NOI, some of which he expressed in his autobiography when talking about the “European influence” and “moral weakness” among Lebanese women compared to the more conservative Saudi women. These remarks were made in April of 1964.

However, his views changed quickly as he continued his travels, and at a press conference a few short months later put forward a more developed understanding:

“in every country you go to, usually the degree of progress can never be separated from the woman. If you’re in a country that’s progressive, the woman is progressive. If you’re in a country that reflects the consciousness toward the importance of education, it’s because the woman is aware of the importance of education. But in every backward country you’ll find the women are backward, and in every country where education is not stressed it’s because the women don’t have education. So one of the things I became thoroughly convinced of in my recent travels is the importance of giving freedom to the women, giving her education, and giving her the incentive to get out there and put the same spirit and understanding in her children. And I am frankly proud of the contributions that our women have made in the struggle for freedom and I’m one person who’s for giving them all the leeway possible because they’ve made a greater contribution than many of us men.”

Malcolm X’s evolving understanding of gender oppression wasn’t a solitary journey—it was shaped by the Black women who mentored, challenged, and influenced him throughout his life. From his mother, Louise Little, a fierce Garveyite organiser, to radical thinkers like Queen Mother Moore, Victoria Garvin, Fanny Lou Hamer, and Maya Angelou, Black women were central to his political education.

Discussions about Malcolm X’s sexuality have gained attention in more recent decades, with some historians suggesting that he may have engaged in same-sex relationships in his youth. Including Manning Marable, in Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, and Bruce Perry in Malcolm: The Life of a Man Who Changed Black America. However, these claims have been met with skepticism, particularly from Malcolm’s family and some scholars, who question their accuracy and the motives behind such interpretations.

Regardless of whether Malcolm X personally identified as queer, acknowledging these discussions is important, not just for historical accuracy, but because Black leaders’ queerness is often erased or downplayed to fit narratives that prioritize traditional masculinity.

Recognizing the complexity of sexuality among Black revolutionaries challenges rigid heteronormative portrayals and affirms that the fight for Black liberation has always included queer voices. Malcolm X’s life and legacy remain radical regardless of his sexual identity, but the conversation itself highlights the broader need to embrace the full humanity of Black leaders without erasing or distorting aspects of their identities.

The assassination in the Audubon Ballroom

In the months before his assassination, Malcolm X knew he was a marked man. The FBI, NYPD, and CIA tracked his every move. Free from the restraint of the NOI, the state feared his potential as a “Black messiah” that could galvanise increasingly radicalised Black Americans.

During his travels to liberated African and Arab former colonies Malcolm X became the de-facto unofficial ambassador for Black America. He was no longer simply a domestic threat but his presence was starting to threaten US imperialism on the world stage. His experiences during these travels led him to draw more clearly anti-capitalist conclusions.

The threats from his former brothers in the NOI didn’t abate either. On February 14, 1965, his home was firebombed with his family inside—a clear warning. He and his family survived, but he knew the end was near.

A week later, on February 21, he was gunned down at the Audubon Ballroom. Among his “bodyguards” was Gene Roberts, an undercover NYPD informer, and despite Harlem’s heavy policing, officers were nowhere to be found. Later investigations revealed the state’s deep involvement, with the FBI and NYPD withholding evidence that could have prevented the killing.

Malcolm’s death wasn’t just an NOI feud—it was a political assassination, sanctioned by a system that saw him as too dangerous to live. J Edgar Hoover’s fear of a “Black Messiah” had been extinguished – for the moment

What the Left Must Learn: Not Assuming Trust, But Earning It

Malcolm X’s deep distrust of white people wasn’t paranoia—it was a hard-earned lesson. And his mistrust extended to the left. Time and again, the white left treated Black struggles as secondary, insisting that class struggle must come first while failing to confront racism within their own movements.

During Malcolm’s lifetime, major unions routinely shut Black workers out, reinforcing economic inequality rather than fighting it. Decades later, the same dynamic played out when Bernie Sanders, despite his economic populism, failed to make racial justice central to his campaigns—costing him critical support from Black voters in 2016 and 2020.

White Marxists and Trotskyists often try to “correct” Malcolm X, and lament that he wasn’t a socialist or speculate on his future political trajectory had he lived longer, rather than learning from him, and his justified mistrust of “the white man”. This arrogance continues to cost the left dearly. Trust isn’t assumed—it’s earned.

There are many reasons Malcolm X never became a socialist or a Marxist – none of them his failings. The state repression faced by Black Socialist and Revolutionary groups, such as MOVE and the Black Panthers, should be a lesson on the vitality of integrating anticapitalism with antiracism. No quarter can be given to self proclaimed Marxists who dismiss racism and issues of oppression as “identity politics” or “moralism”.

The consequences of the white revolutionary left’s failure to fully integrate issues of class and race are stark and have amplified into the 21st century.

The subprime mortgage crisis of 2007/8, was fuelled by predatory lending targeting Black and minority communities, devastated Black incomes and deepened racial and economic inequality.

The Great Recession and subsequent years of austerity widened divisions in the working class, allowing reactionaries like Trump to exploit resentment, while billionaires like Elon Musk can now posture as anti-establishment figures.

The left’s failure to take Black struggles seriously isn’t just a moral failing—it’s a strategic one. Without rebuilding trust and centering anti-racism in working-class politics, the left will remain stuck in a cycle of irrelevance, leaving the door open for reactionary forces to thrive.

Conclusion

Young white people today, particularly young women, are more anti-racist than any previous generation, and their understanding of intersectional oppression gives them a powerful advantage in the struggle ahead.

The Black Lives Matter movement left an indelible mark, proving that real solidarity between Black and white activists is possible. Unlike past movements where white liberals offered only empty rhetoric or offered limited support, BLM saw young white people on the streets, standing alongside Black activists, facing down police brutality and state repression.

The fight against systemic racism is no longer seen as separate from the fight against capitalism—it is understood as part of a broader struggle against oppression in all its forms.

This shift is now deepening with the global movement against the genocide in Gaza. As Western governments and milquetoast liberals offer nothing but performative sympathy, young people see through the hypocrisy, much like Malcolm X did, and they are being radicalised in real time. They reject the limits of tepid reformism and recognise that imperialism, white supremacy, and capitalist exploitation are deeply linked, and must be overthrown.

Malcolm X’s life and death was a mirror and a magnifying glass on the deep entrenchment of racist and imperialism in the U.S. and internationally. He refused to accept what was “possible” within the system and instead fought for what was necessary—a lesson revolutionaries today must take to heart.

But we must be clear: we are not in a revolutionary moment like the 1960s. We are in a period of far right, racist and misogynist authoritarianism ascendancy. where reactionary forces are escalating their attacks on civil liberties, dissent, and working-class power. Yet this only makes our task clearer—the need for a united, organised working class has never been more urgent. The power to smash racism and capitalism lies in our hands. We must seize it and organise. The links between racism and capitalism are ironclad, and both must be smashed. As was often the case, Malcolm X said it best:

“You can’t have capitalism without racism. And if you find a person without racism and he’s a capitalist, he’s like a bird without wings. He can’t fly. It is the system that is the problem. You can’t have capitalism without racism.”